Guiding Lights of the Lower River Passage along the St. John River

About the Lighthouse Route

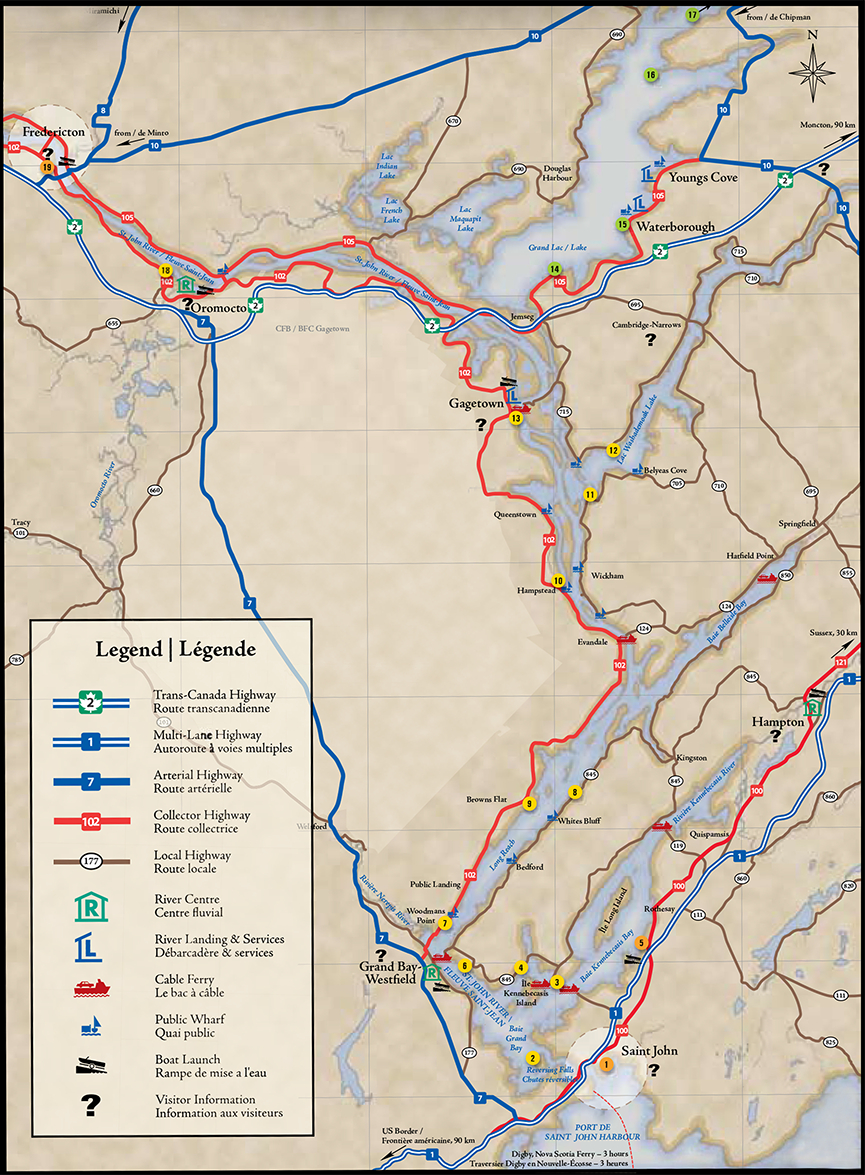

Lighthouses are usually associated with coastal navigation, warning of unseen hazards and guiding ships at sea in their approach to land. Yet lighthouses abound along the St. John River as far inland as Fredericton.

Here in the Lower River Passage, working lighthouses indicate that the river, too, is a navigable waterway. The many decommissioned lighthouses serve as reminders of a bygone age when the river was the key transportation route. This is the only place in Atlantic Canada — and one of the very few places in Canada — with an inland system of lighthouses.

1. Market Square, Market Square, Saint John

2. Green Head (Swift Point) (1869)

Active, tallest lighthouse | Actif, le plus haut phare (15 m), Chemin Greenhead Road,

West Saint John Ouest

3. McColgan Point (1914), Active | Actif,

Chemin Summerville Road, (off | près de la Route 845) Summerville

4. Bayswater (1914), Active | Actif, Route 845, Bayswater

5. Rothesay, Rue Wharf Street (off | près de la

Route 100), Renforth

6. Sand Point (1869), Active, tallest structure |

Actif, la plus haute structure (18 m), Chemin Sand Point Wharf Road (off | près de la Route

845) Sand Point

7. Belyeas Point (1882), Active | Actif, Chemin Morrisdale Beach Road (off | près de la Route 102) Morrisdale

8. The Cedars (1904), Inactive | Non actif

Route 845, Long Reach

9. Oak Point (1869), Active | Actif, Chemin Oak

Point Road, (off | près de la Route 102), Oak Point

10. Hampstead (1900), Inactive, smallest

lighthouse | Non actif, plus petit phare, Chemin

Hampstead Ferry Road (off | près de la Route 102) Hampstead

11. Île Lower Musquash Island (1875), Inactive,

water access only | Non actif, accès nautique

seulement, Île Lower Musquash Island Colwells Creek (entrance to | entrée du lac Washademoak Lake)

12. Hendry Farm (1875), Inactive | Non actif

Hendry Lane (off | près de la Route 715) Lower Cambridge

13. Gagetown (1895), Active | Actif, Ferry Road

(off | près de la Route 102), Gagetown

14. Robertson Point, Modern light - active navigational aid | Phare moderne - feu directionnel

actif, Chemin Robertson Point Road (off | près de la Route 105) Whites Cove

15. Fanjoy Point, Modern light - active navigational

aid | Phare moderne - feu directionnel actif, Chemin Fanjoy Point Road (off | près de la Route 105) Waterborough

16. Cox Point, Modern light - active navigational

aid, not readily accessible | Phare moderne - feu directionnel actif, difficile d’accès

Chemin Cox Point Road (off | près de la Route 10), Cox Point

17. Hawkes Point, Modern light - active navigational aid | Phare moderne - feu directionnel actif,

Chemin Salmon River Mouth Road (off | près de la Route 10), Coal Creek

18. Wilmot Bluff (1869), Inactive, private property, visible from the road | Non actif, propriété

privée - visible depuis le chemin, Chemin Thatch Road (off | près de la Route 102), Lincoln

19. Rue Regent Street, Museum & gift shop |

Musée et boutique souvenir, 615 rue Queen Street (bottom of | au bout de la rue Regent

Street), Fredericton

The Lighthouses and the River

Lighthouses are usually associated with coastal navigation, warning of unseen hazards and guiding ships at sea in their approach to land. Yet lighthouses abound along the St. John River as far inland as Fredericton.

Here in the Lower River Passage, working lighthouses indicate that the river, too, is a navigable waterway. The many decommissioned lighthouses serve as reminders of a bygone age when the river was the key transportation route. This is the only place in Atlantic Canada — and one of the very few places in Canada — with an inland system of lighthouses.

The very earliest guiding lights were not lighthouses at all, though some of them were located at, or near, points where lighthouses were later built. These first lights were known as “mast lights” and consisted of a flagpole with a lantern hoisted to its top each evening.

Along with location, they shared another characteristic with lighthouses: the need for a lightkeeper. Someone, almost always The Lighthouse Route La route des phares 3 a nearby farmer for convenience, made sure that the lantern was fueled, lit, hoisted up the pole, and taken down and extinguished each morning.

Lighthouses were important for the navigation of steamboats but were slow in coming to the Lower River Passage. The first steamboat, built in Saint John, began service between Saint John and Fredericton in 1816. Nine years later, it was joined by another vessel, and by mid-century, a whole fleet was carrying more than 50,000 passengers — along with quantities of freight — on the river annually. Two years after Confederation, in 1869, the new government of Canada took responsibility for inland navigation, and six lighthouses were constructed between Saint John and Fredericton. Some of these “original six,” like Wilmot

Bluff, were proper lighthouses; others, like Sand Point, were mast lights, later replaced by towers.

From these humble beginnings, the network expanded, eventually by 1914 reaching 21 lighthouses. By then, however, the steamboat era had peaked. First railroads and then motor vehicles offered year-round competing transportation. Many of the lighthouses became redundant and, one by one, were taken out of service. Today, a dozen of the original buildings remain, and seven of them continue as operating lights, still guiding navigation in the Lower River Passage.

A Trip on the River

Leaving Saint John by water and pointing the bow upstream, mariners and recreational boaters steer for the “leading light” at Sand Point, which marks the route upriver. Sand Point has been described as the “strangest looking light in the province,” a lighthouse on a high steel red lattice frame. Built in 1897, it resembles no other existing New Brunswick lighthouse, though several now-demolished coastal ones were built to the same innovative pattern. Like most of the Lower River Passage lighthouses, it was constructed by a local builder: in this case, G.W. Palmer, whose costs amounted to $699. The Palmer family appears to have been lighthouse specialists. Two local men of that name built several of the surviving structures along the Passage and others were early lightkeepers.

Back to the east, the lighthouse at Green Head (Swift Point) is half of a point-to-point navigation system, guiding vessels past South Bay, Grand Bay and the Kennebecasis River. Marking the curve around the bay is its other half, Bayswater light. Near the mouth of the Kennebecasis, the McColgan Point lighthouse marks the entrance to Milkish Channel, which separates idyllic Kennebecasis Island from the Kingston Peninsula.

The Belyeas Point lighthouse — whose first keeper was Spafford Belyea — is located at the extreme end of the point, at the lower end of Long Reach, near Grand Bay-Westfield. Intended to guide vessels away from Purdy’s Shoal on the far side of the river, it was one of the most expensive lighthouses to construct, with a cost overrun of more than 50 percent of its budgeted $800. Belyea’s Point, which has been repaired many times following spring flooding, or the locally known “freshet,” continues as an important navigation light in the Lower River Passage.

Oak Point, above Grand Bay, is one of the most strikingly picturesque lighthouses on the river. It can be seen from 20 kilometres away in any direction of approach by water. Constructed in 1869, Oak Point is also the Passage’s second tallest lighthouse, its square white wooden tower

measuring 14.6 metres, from its foundation to the ventilator on its lantern.

The square, box-shaped lighthouse at Hampstead is one of the smallest in the province. It was constructed in 1914 by G.W. Palmer at the precise of cost of $188.96, and was first kept by E.B. Palmer (probably a relative of the builder). The Hampstead light was neither a navigational nor a hazard light, but mostly served as a dusk and night beacon to mark the location of the wharf beside which it stood, a guide to the steamboats then common on the waters of the Lower River Passage.

The entrance to Washademoak Lake, one of the long narrow bodies of water reaching inland from the St. John River and a summering place for generations, is marked by the Lower Musquash Island lighthouse and its companion, the lighthouse at Hendry Farm. Both were constructed in 1893 by John Jones, who won the joint contract with a bid of $675. The lighthouses remain standing today, though the Lower Musquash Island light has been rebuilt several times following high freshet years. Both lights were taken out of service in 1994. The Lower Musquash Island lighthouse, whose pastoral island location renders it accessible only by boat, is now owned by a local preservation group.

Like the Lower Musquash Island lighthouse, the Gagetown lighthouse is raised on stilts. This design helps buildings in low-lying sites cope with the dangers of the annual spring flood when river levels can rise

several metres. It was constructed in 1895 at the mouth of Gagetown Creek to replace an earlier lighthouse, lost in the flood of 1894 on the other side of the river at No Man’s Friend Point — a name that is a warning in itself. The theory behind moving the light across the river was that this site would better withstand flooding. That theory received a blow when the new light was washed away in a freshet five

years later. It was replaced, and then washed away again the following year! This time, a temporary signal of a lantern in a nearby elm tree was substituted, and the lighthouse was rebuilt on stilts to allow flood waters to pass beneath. Gagetown is still an operating light, visible both upriver and down, and it is the furthest inland of any of the Lower River Passage lighthouses still operated by the Coast Guard.

The now privately owned light at Wilmot Bluff is an excellent example of a typical river lighthouse. It was built in 1910 by John C. Palmer at a cost of $1,060 and replaced an earlier mast light. Its square pyramid tower and white light provided a final navigation mark for steamboats bound upriver to Fredericton. This design, sometimes described as “saltshaker,” is considered to be a uniquely Canadian lighthouse style. Decommissioned in the 1960s, the Wilmot Bluff lighthouse is owned by members of the family who were long associated with it as lightkeepers. The lighthouse is on private property and closed to public access, but can be easily seen from the road.

All the original Lower River Passage lighthouses were staffed by local lightkeepers, whose job it was to ensure that the lantern was lit and extinguished daily and that the building and equipment were properly maintained. Most lightkeepers got their jobs through political patronage and seldom retained them after the government changed — though the position sometimes went to another relative whose voting habit matched the new reality, keeping the income in the family. And the income was important — a reliable source of cash for often cash-poor farmers. Not uncommonly, the actual work of keeping the light was done by the wife of the keeper of record. Sometimes a widow even succeeded her husband in the position, as when Clotillie May Bissett took over The Cedars lighthouse on the Kingston Peninsula in 1932, becoming the first female keeper of record, at a salary of $150 a year.

The lighthouses of the Lower River Passage, unique heritage buildings and working beacons alike, welcome visitors to the region by land or water and remind us that this scenic river was, for more than a century, also a busy transportation route.